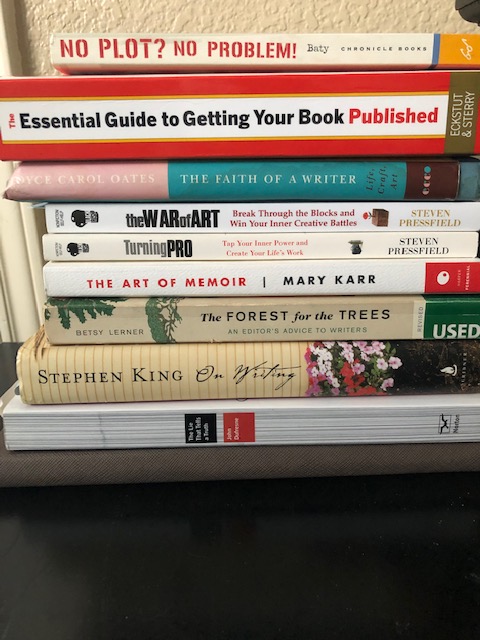

When I consider my 34 years of teaching, I think one of my most important challenges was understanding and supporting each of my teen-aged readers and writers. As an English teacher, I see the task of “getting to know your students” as a Herculean job since we also have to grade and give useful feedback on their essays and research reports.

My students often shared things in their personal narratives that shocked, saddened, or confused me. (And I’m NOT talking about the handwritten scribbles without punctuation or capitalization or the cursive that is so tiny I needed either direct sunlight or a magnifying glass to figure it out). I’m referring to the loneliness, the trauma, the heartaches, and the stress they routinely shared in their essays. I’m remembering the stories that made me cringe, laugh aloud, and cry. I’m remembering the ones that called for an after-class conference or a visit to the school counselor.

I felt both honored and burdened by their honesty. Since high school teachers often have rosters with 180-plus students, how do we learn their names before back-to-school night? How do we handle so much angst, joy, depression, immaturity, intelligence, and cynicism without giving up every second of our home lives? And how do I separate each school day’s drama from my family responsibilities? How do I focus on my own children’s needs and forget my students’ issues?

Like the tv series Severance where Lumon employees sever the connection between their work lives and their private lives. A worker’s “innie” doesn’t remember anything about his/her “outie” home life (and vice/versa). Maybe a teacher could cope better if her “outie” forgot all the details of her “innie” life.

I’ve taught over 6,000 students, and I confess I don’t remember every single kid. But so, so many smiles, smirks, glares, and empathetic nods remain. The ones who shared their wisdom and laughter stay with me as much as the ones who made me cry and rush to another teacher or an assistant principal for help. The faces, of course, linger longer than the names.

Here is a short account of one of my students. Using a different name, this is a brief remembrance of an unforgettable freshman at Crockett High School.

Thomas

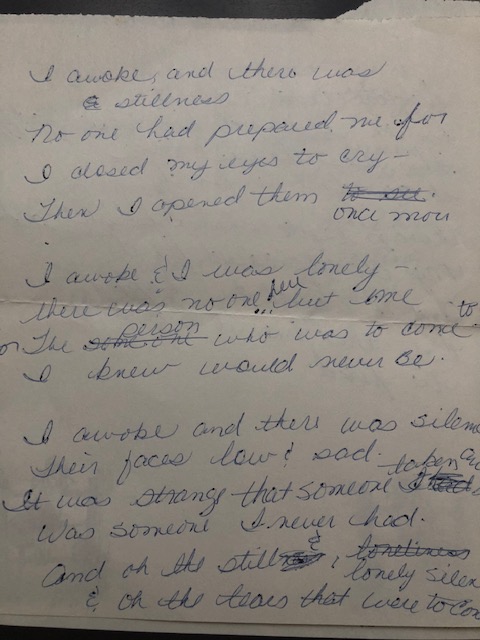

Three weeks into the school year I noticed a freshman’s black and white marbled composition book on my desk atop fat folders of ungraded quizzes – a writing journal without a name and not returned to second period’s designated shelf where even stacks of non-spiral notebooks gave the illusion of order.

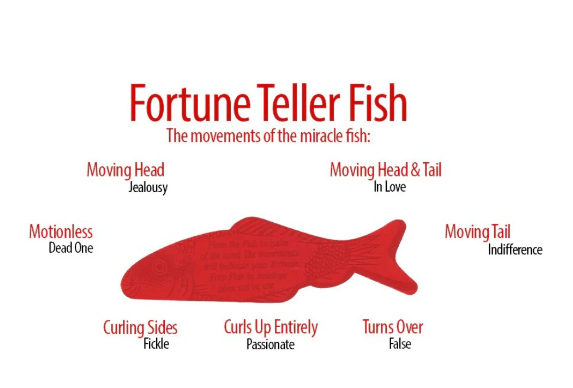

I finished writing next period’s agenda on the streaked white board before I flipped through pages of black ink scrawls that made the lined paper curl like those paper-thin red plastic fish that move in your palm and predict the future. The last few pages had more cursive than print and less punctuation. “i sit on the roof & wonder why im even here” made me sit down. I scanned previous lines about “a heart of hurt,” a girl’s “soulful eyes,” a “silence that slices” and a “cold colorless world.”

I reread the notebook searching for a specific name. Nothing. I flipped through second period’s quizzes searching for that same hard-pressed ink, minimal punctuation, print/cursive mix, and the lowercase i’s until I held Thomas’s quiz about Gwendolyn Brook’s poem “We Real Cool.” He’d circled the poet’s use of alliteration and underlined “We die soon” six times.

I referred back to Thomas’s journal and touched the words “on the roof” before having the sense to seek help. I rushed downstairs to my favorite counselor’s office. The woman who focused on class schedules and state mandated testing switched to doing what she was trained to do. We compared the journal with the quiz paper and agreed Thomas was the author. A slim boy with wild blond curls and a skateboard stuck out of his backpack. He wore over-sized, faded 80’s rock concert t-shirts and loose black jeans. A mix of grunge and emo. Withdrawn yet observant. Someone who sat in the back row, stared out the window, and usually avoided his 31 classmates. Someone a teacher with 184 students could fail to notice.

My vague answers to the counselor’s specific questions made me squirm. We labeled Thomas a smart student with a “B” average, neither a joiner nor a trouble maker. He melded into crowds of teens struggling to be seen and ignored at the same time.

I thought about next week’s Back-to-School Night when tired parents would come to Crockett High School to trudge up and down stairs and visit eight teachers who might remember half of their students’ names, so the question “How’s my son doing?” was as pointless as “What’s my kid’s blood type?”

By now I had missed my lunch duty and had eight minutes before third period began. The counselor kept the journal and nodded to me while reading details about Thomas’s classes and his family on her computer.

I left her office, walked through the school’s open-air courtyard, and looked up past the massive oaks and concrete steps that led to my second floor classroom. Could Thomas be on the school roof? Or across the street atop the flat tops of the strip mall businesses? Had he gone to the neighboring city park’s rec. center next to an empty swimming pool with a peeling, cracked blue bottom?

At my desk I ate broken Pringles from a plastic baggy. I thought of the one time Thomas had spoken up in class telling a peer to “quit stereotyping the story’s protagonist.” My teacher heart had danced a jig then, but I couldn’t remember the rest of the literary discussion. I thought of Thomas’s extra dark eyes beneath long bleached curls and how he responded to my morning greetings with eye contact and head nods.

The assault of third period’s buzzer-bell sent me to my door to greet 33 teens. My after-lunch sophomores came in loud and messy. Conspiratorial laughs from two girls preceded a running Sam who tossed a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos to Carlos who tugged on a cheerleader’s backpack which made her yell, “Loser!” before swatting at the runner who headed toward a window past short, short Cici who wore headphones and slipped into her desk before putting her head down while a new girl taller than me stopped at my door. New girl’s thin hand with chipped black nail polish held a printout from the attendance office. I gave her a smile and a “Hey there,” took the paper, and pointed to my last empty desk. When Gabriella began passing out the black and white journals, I forgot which chapter of Animal Farm we were on because all my head could do was scan rooftops for a fourteen-year-old boy I hardly knew.

Note to readers: The school counselor did locate Thomas off-campus that day. He was hanging out in Garrison Park and despite his broken heart he was fine. She talked with him, but I never confronted him about the “sitting on the roof” drama. He passed freshman English and graduated a few years later. I have no further info. but I hope he remembers some of the literature we talked about like I’ll always remember the panic I felt about the journal he had left on my desk and my flawed attempt at “getting to know my students.”