For one long-fast year of my life, I taught kindergarten in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Estes Hills Elementary School was nestled in a mixture of pine and oak trees and was an older school with character, and lots of other characters who worked there. Each of the classrooms had a back door that opened into a lush courtyard and a front door that lead to a winding sidewalk that circled the school.

The year was 1991 and was one of the most interesting, AKA hard, years of my adult life. 1991 involved a marriage, a move to North Carolina from Texas, a job change and a pending divorce. 1991 was dashed dreams, sour grapes, and a river of tears all rolled into one. Twelve months of shock and awe. 365 days of “What the hell?”, yet there was a calm, deliberate sweetness that awaited me every morning when I greeted my 25 little charges. Estes Hills and the 25 Honeybees (our class nickname) gave me purpose and life.

Estes Hils was a neighborhood school that was also near The University of North Carolina. Many professors’ children attended our school and for that reason, most of the teaching staff was a mature, seasoned group, able to provide the level of learning our clientele demanded. Each teacher was assigned a teacher assistant to help facilitate classroom learning and discipline.

I was one of several kindergarten teachers that year, and we were each assigned 25 students. While you may not think 25 students is a lot, 25 five-year-olds is.

My students were eclectic, coming from varied backgrounds and nationalities. One such student, a handsome little boy named Xolani, came from Africa and had a click language dialect. While he spoke perfect English, his P sounds had a click, which made his language both fascinating to listen to, and hard to understand.

My teacher assistant, Violet, had her master’s degree in art. Every day she planned an art project for our students and during that hour, she took over and I assisted. She was talented, creative, and best of all, patient with a great sense of humor.

Being new to this school that was so steeped in tradition and culture was like being drop kicked through the goalpost of life into another era. It didn’t help that I was from Texas. The North Carolinian women were Berkenstock wearing, clean faced southerners who sounded like they used a question mark at the end of every sentence, with slow paced, elongated v o w e l s. And even though I had the usual slow, Texas drawl, they proceeded to make fun of my y’all’s and fixin to’s, like I was the one with an accent.

It didn’t help that in 1991 I was still sporting big hair, red lipstick and against the wholesome scrubbed look of the other teachers, I looked, well… a little on the trashy side. A little too made up for their taste.

“You Texans,” and they would just shake their heads.

“You Texans think everything is bigger in Texas.”

Quite frankly, my self-esteem was already in the toilet because of my horrible, no good, very bad year. But it was hard to make friends, and by the third day of school, I was feeling like the Lone Texas Ranger and would probably be eating lunch by myself for the rest of my life.

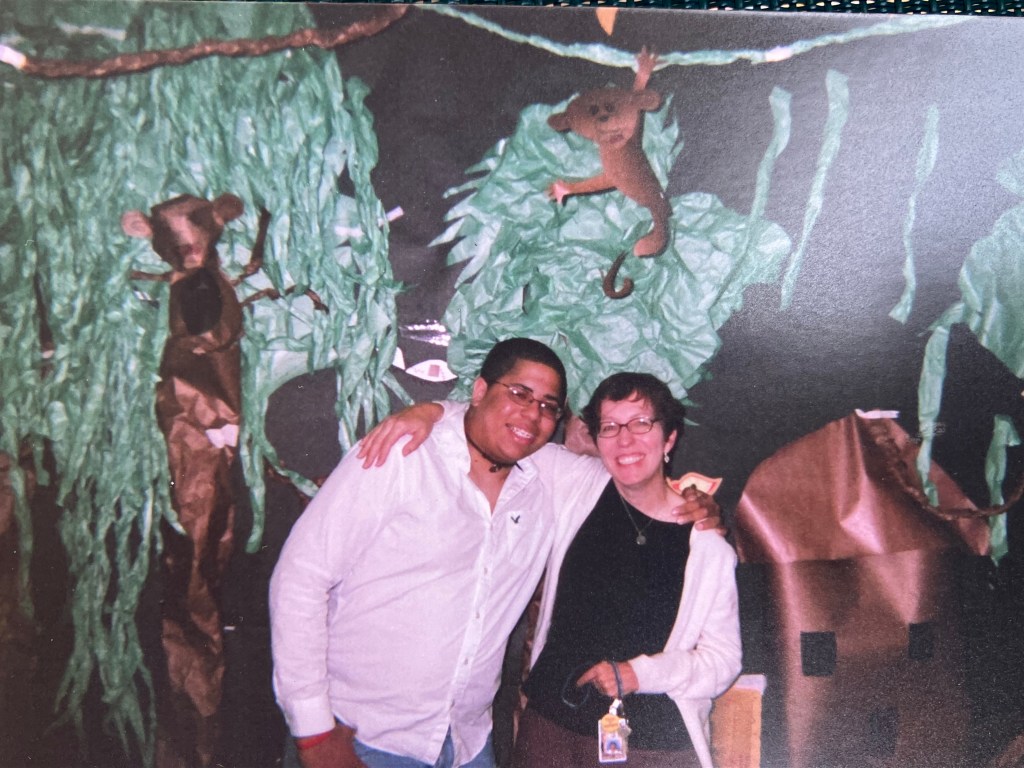

But on the fourth day, my back door swung open and the teacher from two doors down popped his head in.

“Hey, Miss Texas, want to join us for lunch?” Bryon asked.

And a friendship was made.

Bryon and Chris were the two gay teachers from two doors down. They were charming, hysterically funny and comforted my shaky soul like a bowl of chicken and dumplings. We ate lunch together, chatted at recess and they even invited me to some of their fabulous weekend parties. At a time when I felt very little mercy from life, they gifted me friendship and laughter. And when the end of school came, and the end of my marriage, Bryon and Chris helped me load my U-Haul trailer for the long drive back to Texas.

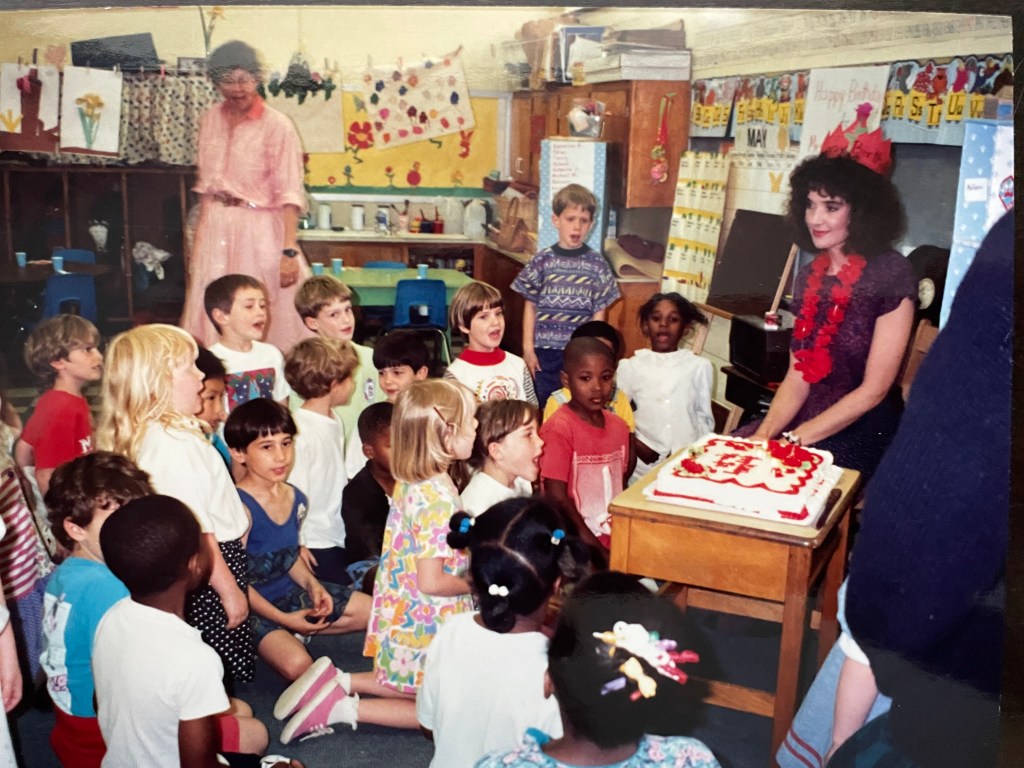

My 25 Honeybees were sweet with not a stinger among them. The parents and students even surprised me with a cake and gifts on my thirty-ninth birthday, and as their joyful voices sang happy birthday, I held back tears from the sheer preciousness of that moment.

One particular day I was leading a lesson about North Carolina as a state, and we were coloring pictures of the flag.

One student raised his hand and asked, “Teacher?”

“Yes, Samuel,” I said.

“Are you a Democrat or a Puerto Rican?”

“You mean Republican?” I asked.

“No,” and he shook his head, “I’m pretty sure its Puerto Rican.”

“Well, which one are you?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m black,” he said

“Cool.” I answered. And I gave him a big hug.

The hug seemed to suffice him as an answer, and we finished coloring in silence.

My long-fast year in North Carolina was a blessing in so many ways. I found out that some people aren’t who they say they are, and that actions really do speak louder than words. I learned it’s ok to be from Texas and proud of it. I marveled at the resilience of the human spirit and the inherit kindness that restored my faith in man. And with great fondness, I remember 25 little Honeybees who needed me as much as I needed them.